The resignification of a fade to black

I returned to Spain from Australia to watch my father die. While grieving, unable to return to Australia and in COVID lockdown, I watched hours and hours of raw footage he had filmed during my childhood. Slowly, a new film started to form. One about loss, and grief and depression and shame, about the silences we kept as a family. But also, one about the point of view, about using cinema to build realities. My best friend observed that I did not only return for my father and to support my mother, but also to reframe my own story in the best way I know how: through filmmaking.

It’s been an 18-month journey to bring my nascent idea to life. Turtle Time – is the result, a feature documentary in development. It tells the story of my dad, Salvador, through his own footage. It also tells my story, how his depression rippled across time. How I escaped but was never free.

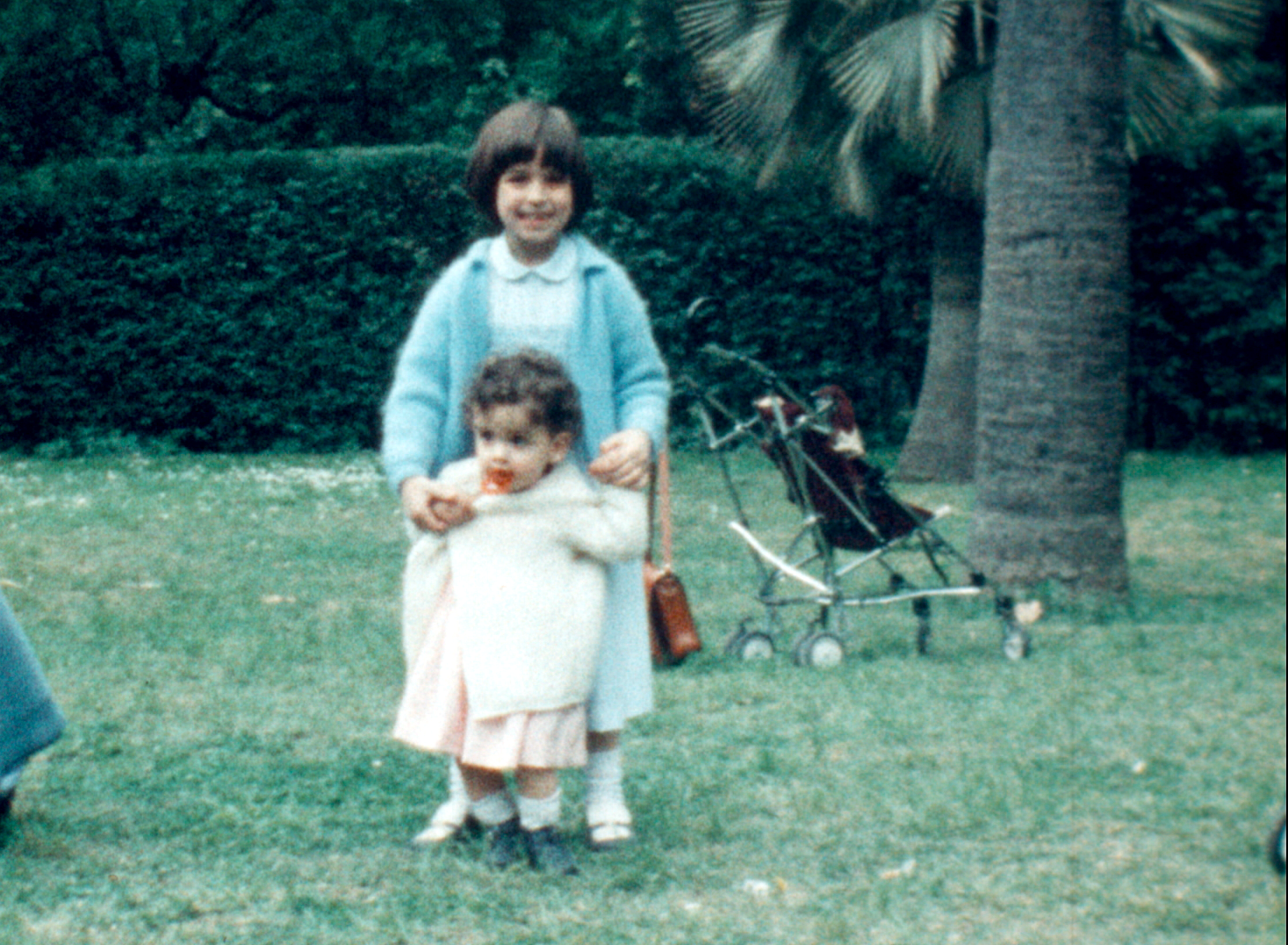

A little more about this footage: My dad filmed me and my four siblings throughout our childhood. He shot tons of footage, all in different formats over the years, that reveals a vital and passionate man, who recorded what he regarded as his perfect family. He was an unacknowledged filmmaker, a prolific director who left a legacy of memory. There’s my brother’s birth, filled with details. Weddings. Trips, animals and nature. He experiments with light and speed. The love and fascination he had for my mother are tangible. And behind the scenes, his captured commentary, our interactions with him.

It took me watching his unfinished film to realise how similar we were. He searched for connections and used his camera to do it. The link between storytelling and identity was strong. If you think about it, ‘I’ and ‘eye’ are pronounced in the same way. Equally, being an amateur filmmaker is quite loaded as a statement. In fact, in Spanish, ‘amar’ means ´to love’, which is what my dad, in his amateur filmmaker hat, did through his practice: to love through filming.

At 45 depression split dad in two. The man who made connections possible, disconnected from himself. He quit filming, and with that, stopped looking at us both through the camera, and in life.

After dad died just 2 years ago, I watched his footage and remembered that fade to black, that time when he split in two, because there were no more tapes. There’s a void.

In the documentary film The Wisdom of Trauma (Zaya & Maurizio Benazzo, 2021), Dr Gabé Mate says: “Every human has a true genuine authentic self and trauma is the disconnection from it, and the healing is the reconnection with it”. Through this film I explore that unfilmed space, that black, that silence within my family. I left Spain to escape the pain of it, but what did my family do? We never talked about it. How do we begin now? What is the best way? ‘Turtle time’ looks for answers behind the silence. It allows for space so that a rift in our family can be revisited and maybe even healed.

Untangling the weight of the untold on camera – either directly or more subtly– is central to my film practice.

Our previous feature film Singled [Out] (Spain/Turkey 2017) sought to understand the stigma around single women in the twenty-first century. It was a project that emerged from a very personal space – my own experience of being single and coming to terms with it. In the modern world, it seemed being single had become acceptable, but we had a hunch it wasn’t true. The documentary shone a light on the damaging, subliminal messages pushed on unmarried or uncoupled women. Through personal stories it showed a broader truth how single women who are happy and unwilling to pair up are a threat to the stability of the system.

Just like Singled [Out], Turtle time is personal, and uses my story to understand the impact of my dad’s illness, and the silence that followed. We wanted to ignore it, but it’s played out in so many ways. Similar to my previous work, it also seeks to illuminate a wider issue of how there is a real collective trauma that happens. By not tackling it, by leaving it unacknowledged, we recreate the trauma all over again.

The film reimagines the role of sadness, in art and in life. As Jonas Mekas reflected on The Diary film: “What it is, really, is that in most cases, in art, sadness is eliminated as part of human experience, as if there were something wrong with it. But there is nothing wrong with sadness. It’s a necessary, essential experience. Sadness is a state that is very real. We need it”.

But Turtle time is essentially an essay of the view of childhood through the eyes of a dad, and how he tried to film a space to ‘live’ that space, creating a space to return. It displays his willingness to capture what can’t last forever.

After all, and quoting Rilke: the only country that man has is his childhood.